Abstracting the Battlefield

Recently I noticed an increase in the number of blog and Facebook posts about '3x3' gaming. Wondering what it was I did some more research and found that it is basically abstracting the battlefield away into a square gridded battlefield of 3 squares by 3 squares (hence '3x3'). Actually, it is slightly more complex.

As you can see in the diagram above, the board is comprised, by row, of you side's Reserve area, your baseline, the center 'no-man's land', your opponent's baseline, and your opponent's Reserve area.

The board is further sub-divided into a left flank, center, and right flank. This effectively makes nine separate positions where units can maneuver and fight one another. All area terrain would be contained within a grid, thus defining the terrain for all of that particular grid location; there would be no areas within a grid where units would be 'in' the terrain while others were 'out'. Linear terrain would generally take the form of being 'on the lines' between areas.

The reserve areas are considered off-board and touching the left flank, center, and right flank of that side's baseline row.

Generally movement is simplified to foot troops moving one grid orthogonally (never diagonally) and mounted, fast, or vehicular units moving two grids. Close combat occurs by moving into the enemy's grid, small arms ranged combat is one grid away (again orthogonally), and longer-ranged weapons two or more grids away.

Although these boards are represented as a grid of squares, I consider this more of an area movement game than a square gridded game, but that is me.

The more I thought about this 'new' style of game, the more I realized that I had played it before, more than two decades ago. The game was called Dixie and it was a card-based wargame put out by Columbia Games. As a game Dixie was simple, but fun, but what hurt it was that Columbia Games was trying to capitalize on the collectible card craze that Magic the Gathering had started and had produced randomized decks, making it more expensive to collect the whole series. (They later realized the error of their ways and produced full sets people could buy, but I think it was too late by then.)

Dixie came out with three versions, each representing a different battle in the American Civil War, but all followed the same basic rules. The image above shows the abstract battlefield that it used. You will note the similarities to the 3x3 format. The primary difference is that there is no 'no man's land', or middle row. Each side goes straight from its baseline to the enemy baseline.

Dixie did add an advanced rule that allowed a player to make a flanking attack, moving straight from the reserve (the player's card hand) to the enemy's left and right baseline area, but these flank positions were not proper areas where units were held; it was more of a visualization to help you understand how a unit could go straight from the reserve to the enemy's baseline.

Another game that drew upon this concept — and gave credit to Dixie as inspiration — was GMT Games' Sun of York, also a card-based wargame, only this representing the battles of the War of the Roses.

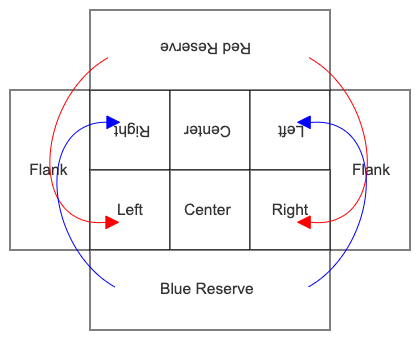

As shown in the image above, this has been the most 'complex' of the designs to date (that I am aware of). It is similar to the 3x3 model, having three rows and three columns, along with a red and blue reserve, but also having separate red and blue flanking positions. Further, the flanks contain units and those units can push into the enemy flank positions. (No combat occurs on the flanks, however.) As with all other formats, you can never push units into the enemy's reserve area.

Conceptually, I think I actually like a mixture of the Sun of York and Dixie models. I like the single flank areas of Dixie, but I prefer them to be actual positions where units are posted. The archers in the woods at Agincourt come to mind. I do prefer the 3x3 grid for the main battle area that both 3x3 and Sun of York share. I am not sure why 3x3 does not account for flanking attacks. Perhaps because it envisions itself as being a portion of the total battlefield while both Dixie and Sun of York are reflecting the entire battle?

Another element that might define the scope of the action is the stacking limit applied to each cell of the grid. I think most players allow only two units in the 3x3 model while both Dixie and Sun of York allow four (plus Leaders).

Representing Campaigns and Battles

Recently I started playing Marvel United (MU) — a superhero versus supervillains game — with my wife (she has taken pity on me while I am still recovering from foot surgery and cannot go out and game with others) and it also abstracts the battlefield. If you think about the storylines in comics it is generally a series of battle vignettes in various locations between the superheroes and the supervillain's henchmen, with an occasional short fight between the superheroes and the supervillain before a final big fight between them that generally (hopefully) ends in the supervillain's defeat. MU models that by making each area of the map a different location where battles can occur, with each location not being broken down any further as these are not mass actions but rather skirmishes between a few people on each side.

Characters move around the map (shown in the image above) from location (six large squares arranged in a circle) to adjacent location, clockwise or counter-clockwise, with some characters able to move to any location due to their powers (typically flying) or equipment, fighting the opponents found there. Once enough missions have been completed (defeating thugs and henchmen, rescuing civilians, performing heroic tasks, etc.) the final battle can commence and the superheroes can start dealing damage to the supervillain. It is a very interesting game model that I will be reviewing on my Solo Battles blog at some point, but I think it shows an innovative way to reflect the cinematic battles that occur over time, but not the same location.

Summary

Games like these allow players to quickly fight battles and get to a decisive result very quickly, minimizing the fuss and muss generally required with rules that have players carefully measuring movement and ranges, changing formation, and jockeying for position to optimize tactical effectiveness. In these games simple rules determine how units within an area face off and combat one another. The most optimal formation is considered to be automatically used by the unit commanders (which you are not; you are the overall commander), so all such details are abstracted away.

If you like these sort of games, they not only allow you to get into and resolve them very quickly, they are often designed to be gamed in a smaller space, such as a folding table. I personally like them because they also allow you to stay seated for most of the game, much like a board game does. But that is because I am an old man who will have back pain by the end of a multi-hour gaming session.

If you have seen other format of these area-type game boards, let me know. I know that the AWI miniatures rules that I reviewed, The World Turned Upside Down, promised to be an area map battle game, and that was what definitely drew me to it initially. Ganesha Games' Of Armies and Hordes is similar to MU in that the areas are more for the campaign and the battle is fought out in that single area location. You could easily combine those campaign rules with something like the 3x3 model to 'zoom in' and fight out the battle once you determine which area on the map the conflict occurs. (Hmmmm...)

Wargames are Puzzles

Recently I watched a video on how to play MU and the narrator said "Marvel United games are basically giant puzzles. You pick the supervillain that you are going to fight and they have specific characteristics — henchmen, attacks, hit points, ways they can be defeated, victory conditions, etc. — that you look at the determine which team of heroes and tactics you should select to defeat them. That is the puzzle solving part of the game experience." I thought about that and recognized that wargames are effectively the same. They are complex puzzles to be solved.

I know that when I wrote about Tactical Exercises and Micro-Games back in 2011 I was alluding to this idea. When you have the task of taking a house (skirmish) or a town (mass battle game) within a larger battle, the taking of that structure is a puzzle. There is a certain way to approach the task, you need a certain amount of troops compared to the defending force. You run these micro-games performing these singular tasks in order to understand the 'formula' for success.

For example, when I was 13 or so and playing Column, Line, and Square (CLS, a figure-heavy set of Napoleonics rules) I would generally bash my troops against a town trying to take it and always losing. One day an older gamer said "let's just play you attacking a town" rather than playing a larger game that had all kinds of elements, like roads, woods here and there, some walls and hedges, and so on. He said all that other stuff are distractions. "Right now, you need to focus on how to take that one building." So, that is all we had on the board, one building and nothing else. He took some points and bought Russians and I had more points (because I was attacking) and I bought some French. Got slaughtered. Rand it again and still got slaughtered. He said "Why were you slaughtered?" I realized the math of the situation — the minuses I had to contend with for firing at troops in cover — and came to the conclusion that if I truly needed to take the house, I did not have enough troops to overcome the penalties. So we started playing the same game with me getting increasingly more points. Eventually I won and I came to realize that there are some puzzles you cannot solve, i.e. attacking a town in CLS with only a 4:3 point advantage will always result in a loss, so the winning move is to figure out how to not attack the town. After that weekend of playing the same simple battle a dozen times and reaching my Eureka moment, I became a much better player. That was also when I realized that I liked wargames not because I like playing games, but because I like solving puzzles.

The problem with many rules though is that they throw so many variables into the mix, then beat the puzzle right out of the game. Most players cannot work through the probabilities of a dozen turns worth of dice rolls to determine the odds of winning. (I certainly cannot.) Adding other factors like troops defending terrain (-1 to firing for cover), and whether they will even be able to reach that cover before you have a chance to fire (because of variable movement rates) and many rules get reduced to games of chance. Don't get me wrong, I am not saying to remove all elements of chance (although I do play and did review various deterministic rules), but some rules just go to far.

I have talked with a number of gamers, however, that feel the opposite. Whereas I like to analyze games, in fact that is a particularly strong element of my enjoyment of gaming, others tell me that they enjoy more the rolling of the dice and seeing how the battle unfolds. Sure, they like to win too, but if the 'story' was a loss but fun that is far more preferable to a boring win. I have been accused many a time of being too over-analytical and taking all of the fun out of gaming, but that has only made me realize the two general types of players: puzzle solvers and gamers.

What about you? Are you looking for rules that are puzzles or games?